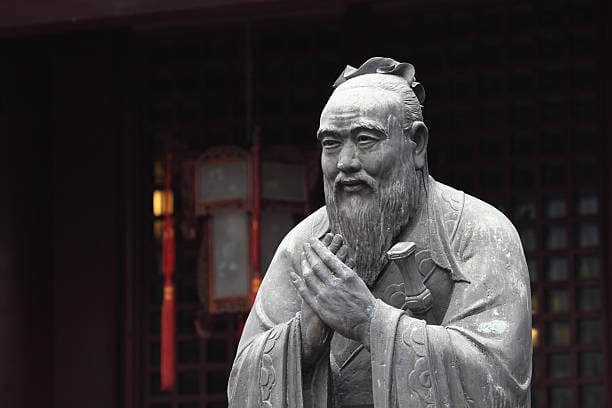

Confucius was the First Prompt Engineer

What a 2,500-year-old teacher can tell us about AI, dialogue, and the power of words

I first encountered Confucius in middle school, through freshly printed versions of The Analects. The Confucius Analects, a slim collection of dialogues between the philosopher and his students, revealed to me one thing about Confucius: he often adjusted his answers depending on who was asking. At times, he spoke in riddles and parables; at times he contradicted himself out of care for the student before him. In one case, he told Zilu to act immediately. When Ranyou asked the same question, he told him to wait. Two and a half millennia later, we call this practice prompt engineering. If history tells us anything, it’s that the words we choose and the questions we ask shape the answers we end up living with.

子路问:“闻斯行诸?”

子曰:“有父兄在,如之何其闻斯行之?”

冉有问:“闻斯行诸?”

子曰:“闻斯行之。”

公西华曰:“由也问‘闻斯行诸’,子曰‘有父兄在’;求也问‘闻斯行诸’,子曰‘闻斯行之’。赤也惑,敢问。”

子曰:“求也退,故进之;由也兼人,故退之。”

[Modern Translation]

Zilu asked, “When I hear a principle, should I put it into action right away?”Confucius replied, “If you still have your father and elder brothers above you, how could you simply hear something and act on it immediately?”

Later, Ranyou asked, “When I hear a principle, should I put it into action right away?” Confucius replied, “When you hear it, you should act on it.”

Gongxi Hua said, “When Zilu asked, ‘When I hear a principle, should I put it into action right away?’ you answered, ‘You still have your father and elder brothers above you.’ But when Ranyou asked the same question, you answered, ‘When you hear it, you should act on it.’ I’m confused, so I dare to ask for your guidance.”

Confucius said, “Ranyou tends to hold back, so I encourage him forward. Zilu tends to be too headstrong, so I restrain him.”

We can tie Confucian philosophy to today’s large language models through one shared element: dialogue. The conversations recorded in the Analects predominantly circle around questions of virtue and moral goodness. How can I be a better son? How can I achieve greatness? Am I capable of serving in government? Confucius adjusted his answers to each student’s temperament, phrased in ways that guided them toward the growth they needed most. In today’s AI labs, we’re doing something relatively similar. We’re aligning models so they can produce helpful, harmless, and honest outputs. That’s what reinforcement learning and human feedback (RLHF) really are: a back-and-forth “teaching” loop where human trainers mold the machine’s responses through rewards and corrections. You probably do this with your chatbot!

Before I get ahead of myself, anyone who has spent any amount of time with ChatGPT will know that the way you frame a task makes or breaks the output. If you asked it to summarize a passage, it’d probably return something stiff, academic, and robotic. If you asked it to sound like Shakespeare, it would break into verse. If you asked it to explain physics to a child, it would switch to simple metaphors. The key here is that different instructions produce very different tones; in other words, the outcome depends almost entirely on the words you choose at the start.

“If names are not correct, speech does not accord with truth, and affairs cannot succeed.” (Analects)

Confucius believed that language does not merely reflect society but manifests it. Words commit us to courses of action; misnaming distorts not only what we say but also what we do. This is why people in his time, and often in China still, are careful with speech in a way that contrasts with Western free expression.

In a similar sense, this is why Chinese AI companies today call their models “big models” rather than the familiar Western “large language models.” For example, Baidu explicitly markets ERNIE as a 大模型 (“big model”), and not an LLM. "Big models" refers to a worldview that emphasizes AI as scale, as magnitude, as nation-building. Meanwhile, Western naming conventions (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini) lean toward the individual or the mythical. Each and every word choice pinpoints what users would expect, what they can demand, and ultimately what the chatbot produces.

All this raises a provocative question: when we spend hours refining prompts, correcting outputs, and coaxing ChatGPT to deliver our ideal responses, does that make us the teachers of value? Specifically our moral values? Models inherit the biases, ethics, and priorities we encode into their training. And the question isn’t only whether AI can reason, but whose conception of virtue it's being trained to follow.

As prompting has grown more popular, research papers in recent years have increasingly focused on how to best prompt large language models. While that alone is a significant indication of its staying power, it also reflects our utilitarian tendency to exploit rather than to teach. After all, these chatbots were made to boost productivity and serve their useful purposes. Online forums are also filled with “prompt libraries” and one-liners designed to squeeze the maximum output from a model.

If we map Confucian pedagogy onto prompting, the act looks less like “hacking” per se and more like a form of moral instruction or a way of guiding intelligence toward harmony, balance, and proper conduct. Like a teacher who doesn’t simply extract answers from students, a successful prompt cultivates the student’s character, most often through dialogue. By that logic, prompting appears to be more like education than it is exploitation, and you can easily see this contrast in how the two cultures talk about AI (which also hints at where each culture believes AI should go). Prompt engineering in the West is often described as a trick or workaround. But in China, the language leans more toward cultivation: “training,” “guiding,” and “correcting.” This Chinese framing, whether consciously intended or not, situates AI within a longer tradition of shaping minds and aligning behavior, which is honestly more akin to raising a child.

When we call ourselves prompt engineers, we like to imagine we’re doing something revolutionary. But two and a half thousand years ago, Confucius was already showing us that the shape of a question shapes the shape of the answer and, more importantly, the shape of the student. A single phrase can push someone to act boldly or cautiously, to align with truth or to drift off course. That’s why China’s AI culture today feels different from Silicon Valley’s. And maybe prompt engineering isn’t the invention of the AI age at all. It may be a return to something Confucius already intuited: that the form of a question is not overlooked but carries within it the power to direct thought, constrain possibility, and prescribe a certain horizon of answers. If so, what we call “engineering” today is simply the latest expression of an older human practice. Specifically, it involves the intentional application of language to control intelligence, be it human or machine-based.

Confucius wasn’t just a teacher of men. He was the first prompt engineer.