When Canadian company Sandvine (since rebranded as AppLogic Networks) withdrew from the Pakistani market under U.S. sanctions in 2023, it left behind a trove of deep-packet inspection hardware embedded in the country’s telecom infrastructure. Rather than dismantling the surveillance capability, Chinese company Geedge Networks apparently stepped in, retrofitted the existing Sandvine equipment, and built a new, more comprehensive state surveillance and censorship model.

This handoff was one of many operations documented in over 100,000 leaked files from Geedge Networks, a company that has been secretly selling what amounts to commercialized versions of China's Great Firewall to governments worldwide. The leaked documents, studied by a consortium including Amnesty International and other human rights organizations, reveal a vast number of internal communications, technical specifications, and operational logs showing how Geedge has deployed its surveillance systems across at least five countries while testing experimental features, including internet access "reputation scores."

What the files show isn’t just a single company’s work but evidence of how digital control itself has evolved. In the past, large-scale surveillance systems were either developed directly by governments (like China’s original Great Firewall) or required extensive custom integration by foreign vendors. Geedge has taken a different approach; they have created standardized products, like the Tiangou Secure Gateway hardware and Cyber Narrator software interface, that can be deployed across different countries with minimal customization, or at least, compared to earlier bespoke systems, seem very much plug-and-play.

Modern surveillance infrastructure, on the other hand, has become modular and infrastructure-agnostic, meaning it can be grafted onto almost any telecom backbone. In practice, the same core system that is monitoring 81 million connections in Myanmar also operates in Kazakhstan (K18 and K24), Pakistan (P19), and Ethiopia (E21). And once embedded, it’s hard to remove, showing how repression has become standardized, transferable, and essentially permanent once installed.

For example, by October 2024, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority had renewed Geedge's license for the same monitoring capabilities, including email interception. Leaked support tickets show intercepted emails with full content and metadata flowing through infrastructure that Sandvine originally built. It doesn’t matter who manages the infrastructure; it may have been Sandvine in the past, it may be Geedge Networks now, and another company could inherit operations with minimal disruption.

On another note, modern surveillance systems create a form of dependency between nations. Geedge’s equipment sits on 26 data centers across 13 internet service providers in Myanmar alone. This isn’t software that can be easily uninstalled; it’s hardware that sits at the core of how internet traffic operates in a country. In fact, Geedge personnel are to remotely access client systems or travel on-site for repairs. The company even has "senior overseas operations and maintenance engineers" job postings on third-party sites requiring three to six months abroad in client countries like Pakistan, Malaysia, Bahrain, Algeria, and India.

Geedge equipment also required extensive modifications to existing telecom infrastructure: changes to traffic routing, data processing workflows, and network architecture. Removing it would likely be highly disruptive to core telecom infrastructure. When your country's internet monitoring depends on foreign technicians who understand proprietary hardware and software, switching vendors becomes enormously complicated.

This all creates a form of digital lock-in. Once installed, these systems become integral to how a country's internet functions, making the cost of switching prohibitively high and the risks of service disruption substantial.

Another pattern that emerged through this whole situation is that tools that were first deployed in places like Myanmar and Ethiopia later appear in pilot projects inside China. In Xinjiang, Geedge’s systems were adapted with new features such as geofencing and ‘reputation scores.’ While the documents don’t spell out an explicit strategy, they reveal a feedback loop in practice: that foreign deployments are shaping the evolution of China’s own censorship model.

For instance, the Ethiopian deployment shows Geedge's system switching from monitoring to active interference 18 separate times, with the most significant shift occurring just days before the February 2023 internet shutdown. Each transition generated performance data, error logs, and technical adjustments that could inform system improvements.

In Myanmar, the deployment catalogued 281 popular VPN tools, recording their technical specifications, subscription costs, and circumvention effectiveness. Blocking mechanisms were then tested against this database, refining detection algorithms through continuous engagement with actual user attempts to bypass censorship. This created a detailed repository of circumvention tools that Geedge engineers could draw upon in future deployments.

Finally in 2024, after years of overseas operations, Geedge launched its Xinjiang pilot project, designated J24 in internal communications. Documents show collaboration with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, specifically their Massive and Effective Stream Analysis laboratory. Photographs reveal academy students visiting Geedge's Xinjiang server facilities, directly absorbing lessons learned from international deployments. The Xinjiang implementation incorporates features that weren't present in earlier overseas deployments. This deployment incorporated features absent in earlier foreign rollouts, like user geofencing, relationship mapping between individuals, and a reputation scoring system. Taken together, the records suggest these advanced capabilities emerged only after years of overseas operations.

What makes this entire operation possible is how Geedge packages these capabilities. The company markets itself as providing "comprehensive visibility and minimizing security risks" for clients, positioning its services within the framework of cybersecurity and network monitoring. This language deliberately mirrors how legitimate lawful interception systems are described: tools that allow governments to monitor specific communications under judicial oversight or established legal frameworks.

Yet the company's actual capabilities extend far beyond standard lawful interception. Geedge's Tiangou Secure Gateway processes all internet traffic flowing through a country, scanning every packet for content, metadata, and behavioral patterns. The malware injection practice represents perhaps the starkest departure from lawful interception norms. The system not only has the ability to inject malicious code into users' internet traffic but also to monitor and manipulate digital communications.

Another example is a prototype ‘reputation score’ system… It’s not clear whether this feature was ever deployed at scale, but its inclusion in internal testing shows how far Geedge is willing to push beyond lawful interception. Each internet user receives a baseline score of 550, which must reach 600 through submission of personal information, including national identification, facial recognition data, and employment details. Users below this threshold cannot access the internet at all. No established lawful interception framework includes conditional internet access based on compliance scoring.

Perhaps the most sobering realization from this leak is how easily comprehensive surveillance can get packaged as something else. Twenty years ago, building a surveillance apparatus like China's Great Firewall was a massive undertaking that required state resources, and, controversies aside, everyone knew about it. Now, governments, vendors, and civil society all face a choice: accept these systems as neutral infrastructure, or confront the ethical and political consequences of deploying surveillance that far exceeds traditional lawful interception.

Subscribe to get weekly insights on China's tech culture that Western media misses.

As of September 2025, approximately 170 million Americans spend, on average, one hour every day in an app that is designed to maximize psychological grip. While Congress fixates on TikTok’s data collection usages, what hasn’t received enough attention is how the platform has successfully industrialized human attention itself. Where earlier media relied on polished narratives (films with arcs, shows with seasons), TikTok turned culture into a never-ending feedback loop of impulse and machine learning.

TikTok didn’t invent short videos or algorithmic feeds, though. Vine created looping six-second clips in 2013, YouTube has used recommendations for over a decade, Instagram rolled out Stories in 2016, and MTV conditioned audiences to rapid cuts long before any of them. What TikTok did was fuse these scattered experiments into a full-scale system for harvesting attention.

Most platforms’ “For You” pages are far less finely tuned. They adjust slowly, learning from signs like likes, follows, or finished videos. TikTok's algorithm learns instantly from micro-behaviors. You can nuke your feed in minutes just by deliberately watching only one type of video—say, pottery clips or capybara memes. That’s because the algorithm heavily weights engagement signs per video rather than long-term user profiles. Public documentation and leaked papers suggest TikTok may also track micro-behaviors such as how long users hover before swiping away. This results in a recommender system that feels uncannily perceptive.

However, before today, each medium we’ve invented reshaped how we think and consume information. The printing press trained readers in linear, sequential thought, encouraging sustained focus and complex argumentation. Television created visual storytelling and shared cultural moments, with families watching the same shows at the same time and building collective references. The internet introduced hyperlinked thinking, enabling rapid information switching, comparison of perspectives, and knowledge-building through exploration.

Now, the world is picking up on the TikTok model.

News organizations like The Washington Post have invested in and expanded a dedicated TikTok team since 2019, producing short and snappy newsroom videos that regularly go viral. In education, students are struggling with assignments longer than a few minutes and expect information delivered in rapid, visually engaging bursts. In entertainment, traditional stand-up comedy builds tension over minutes before a punchline, but TikTok comedians deliver the absurd immediately — a person discovering their roommate has been using their toothbrush as a cleaning brush — and increasingly structure shows around "clippable moments" designed to go viral. Song introductions have shortened dramatically, with one study finding average intros fell from more than 20 seconds in the 1980s to just five, while movie trailers increasingly resemble TikTok compilations: rapid-fire montages of action sequences and emotional beats rather than traditional narrative setups.

Cultural consumption itself has also become a form of algorithmic training. Instead of browsing Netflix and choosing what to watch, users scroll TikTok to see what the algorithm predicts. This means that you're not consuming culture; you're teaching a machine how to feed you culture more efficiently.

TikTok also rewards hyper-specialization. Entire followings are built on carpet-cleaning videos, paint-mixing shots, or the same dance repeated in new locations. Success comes less from broad talent or universal appeal than from perfecting a narrow niche optimized for the algorithm. In other words, creators who identify and double down on the smallest engagement signals are algorithmically incentivized to specialize, turning micro-content into a precise science of attention capture. This hyper-optimization emerged in markets where dozens of apps competed brutally for user attention. Platforms that kept people engaged survived; the rest died. That evolutionary pressure produced increasingly sophisticated ways to capture attention, and the most successful apps learned to treat human psychology like an engineering problem to be solved through data and iteration.

As American platforms adopt TikTok-style optimization, the format sets expectations for all digital content. Micro-optimization techniques are spreading worldwide, establishing a new standard for how human attention is structured algorithmically. TikTok delivers exactly what we want: immediate satisfaction, personalized content, and endless novelty. But efficiency always involves trade-offs. We gain instant access to exactly the content that triggers our reward systems, but we lose the ability to be bored, to sit with incomplete thoughts, to wrestle with ideas that don't immediately pay off. We lose the serendipity of discovering things we didn't know we wanted.

Are we making this trade consciously? Most users have never considered that their scrolling patterns are training an algorithm, or that their entertainment has been optimized for maximum psychological grip rather than maximum meaning.

The irony, of course, is that if you've read this far, it may mean you’ve already mastered a rare skill: sustained attention in a world of distraction.

Subscribe to get weekly insights on China's tech culture that Western media misses.

Your credit score is social credit. Your LinkedIn endorsements are social credit. Your Uber passenger rating, Instagram engagement metrics, Amazon reviews, and Airbnb host status are all social credit systems that track you, score you, and reward you based on your behavior.

Social credit, in its original economic definition, means distributing industry profits to consumers to increase purchasing power. But the term has evolved far beyond economics. Today, it describes any kind of metric that tracks individual behavior, assigns scores based on that behavior, and uses those scores to determine access to services, opportunities, or social standing.

Sounds dystopian, doesn’t it? But guess what? Every time an algorithm evaluates your trustworthiness, reliability, or social value, whether for a loan, a job, a date, or a ride, you're participating in a social credit system. The scoring happens constantly, invisibly, and across dozens of platforms that weave into your daily life.

The only difference between your phone and China's social credit system is that China tells you what they're doing. We pretend our algorithmic reputation scores are just “user experience features.” At least Beijing admits they're gamifying human behavior.

When Americans think of the "Chinese social credit system," they likely picture Black Mirror episodes and Orwellian nightmares. Citizens are tracked for every jaywalking incident, points are deducted for buying too much alcohol, and facial recognition cameras are monitoring social gatherings; the image is so powerful that Utah's House passed a law banning social credit systems, despite none existing in America.

Here's what's actually happening. As of 2024, there's still no nationwide social credit score in China. Most private scoring systems have been shut down, and local government pilots have largely ended. It’s mainly a fragmented collection of regulatory compliance tools, mostly focused on financial behavior and business oversight. While well over 33 million businesses have been scored under corporate social credit systems, individual scoring remains limited to small pilot cities like Rongcheng. Even there, scoring systems have had "very limited impact" since they've never been elevated to provincial or national levels.

What actually gets tracked? Primarily court judgment defaults: people who refuse to pay fines or loans despite having the ability. The Supreme People's Court's blacklist is composed of citizens and companies that refuse to comply with court orders, typically to pay fines or repay loans. Some experimental programs in specific cities track broader social behavior, but these remain isolated experiments.

The gap between Western perception and Chinese reality is enormous, and it reveals something important: we're worried about a system that barely exists while ignoring the behavioral scoring systems we actually live with.

You already live in social credit.

Open your phone right now and count the apps that are scoring your behavior. Uber drivers rate you as a passenger. Instagram tracks your engagement patterns. Your bank is analyzing your Venmo transactions and Afterpay usage. LinkedIn measures your professional networking activity. Amazon evaluates your purchasing behavior. Each platform maintains detailed behavioral profiles that determine your access to services, opportunities, and social connections.

We just don't call it social credit.

Your credit score doesn't just determine loan eligibility; it affects where you can live, which jobs you can get, and how much you pay for car insurance. But traditional credit scoring is expanding rapidly. Some specialized lenders scan social media profiles as part of alternative credit assessments, particularly for borrowers with limited credit histories. Payment apps and financial services increasingly track spending patterns and transaction behaviors to build comprehensive risk profiles. The European Central Bank has asked some institutions to monitor social media chatter for early warnings of bank runs, though this is more about systemic risk than individual account decisions. Background check companies routinely analyze social media presence for character assessment. LinkedIn algorithmically manages your professional visibility based on engagement patterns, posting frequency, and network connections, rankings that recruiters increasingly rely on to filter candidates. Even dating has become a scoring system: apps use engagement rates and response patterns to determine who rises to the top of the queue and who gets buried.

What we have aren't unified social credit systems…yet. They're fragmented behavioral scoring networks that don't directly communicate. Your Uber rating doesn't affect your mortgage rate, and your LinkedIn engagement doesn't determine your insurance premiums. But the infrastructure is being built to connect these systems. We're building the technical and cultural foundations that could eventually create comprehensive social credit systems. The question isn't whether we have Chinese-style social credit now (because we don't). The question is whether we're building toward it without acknowledging what we're creating.

Where China's limited experiments have been explicit about scoring criteria, Western systems hide their decision-making processes entirely. Even China's fragmented approach offers more visibility into how behavioral data gets used than our black box algorithms do.

You may argue there's a fundamental difference between corporate tracking and government surveillance. Corporations compete; you can switch services. Governments have monopoly power and can restrict fundamental freedoms.

This misses three key points: First, switching costs for major platforms are enormous. Try leaving Google's ecosystem or abandoning your LinkedIn network. Second, corporate social credit systems increasingly collaborate. Bad Uber ratings can affect other services; poor credit scores impact everything from insurance to employment. Third, Western governments already access this corporate data through legal channels and data purchases.

Social credit systems are spreading globally because they solve coordination problems. They reduce fraud, encourage cooperation, and create behavioral incentives at scale. The question isn't whether Western societies will adopt social credit (because we're building toward it). The question is whether we'll be transparent and accountable about it or continue pretending our algorithmic reputation scores are just neutral technology.

Current trends suggest both systems are evolving toward more comprehensive behavioral scoring. European digital identity initiatives are linking multiple service scores. US cities are experimenting with behavioral incentive programs. Corporate platforms increasingly share reputation data. Financial services integrate social media analysis into lending decisions.

If both countries evolve toward comprehensive behavioral scoring, and current trends suggest they will, which approach better serves individual agencies? One that admits it's scoring you, or one that pretends algorithmic recommendations are just helpful suggestions?

When Uber can destroy your transportation access with a hidden algorithm, and when credit scores determine your housing options through opaque calculations, is that really more free than a system where you know at least some of the behaviors that affect your score?

So when China's explicit social credit approach inevitably influences Western platforms, when your apps start showing you the behavioral scores they've always been calculating, when the rules become visible instead of hidden, don't panic.

Because for the first time, you'll finally understand the game you've been playing all along. And knowing the rules means you can finally choose whether you want to play.

Subscribe to get weekly insights on China's tech culture that Western media misses.

When ChatGPT translated a passage from Mo Yan's Red Sorghum, it turned “高粱地里的风声” into “the sound of wind in the sorghum fields.” Which is technically correct, but it’s stripped of the cultural contexts and language brilliance of the original. The phrase evokes a little more than just wind… the cadence of rural life, the intimacy of memory, and the sense of a world on Chinese soil. The AI version conveys the meaning clearly to a global audience, but some of the original’s earthy resonance is inevitably lost.

This is happening to all of Chinese literature. And honestly? It might be the best thing that's ever happened to it.

In 2024 alone, China Literature's translation output exceeded everything they had published in previous years combined with the help of AI. Nearly half (42%) of WebNovel's top 100 global bestsellers now come from AI translation pipelines.

Whereas overseas readership of Chinese web novels surged by over 50% in a single year, reaching 352 million readers and generating three-quarters of a billion dollars in revenue. Spanish-language editions have more than tripled, while European markets that barely had any Chinese literature suddenly have hundreds of titles available.

What's driving this boom isn't just "better technology," though. It's a perfect storm of global curiosity about Chinese stories (thank you, Three-Body Problem and streaming's appetite for international content), AI translation tools that finally sound less like robots, and Chinese web novel platforms realizing they had a pile of untranslated content ready to be transformed.

Before AI translation, Chinese literature lived in a publishing ghetto. A few dozen works per year made it into English, chosen by Western publishers who played it safe with "universal" themes. Brilliant authors writing hyperlocal stories never had a shot. The gatekeepers decided their voices were "too Chinese" for global audiences. Nevertheless, as of 2024, 2,000 AI-translated Chinese works have hit global markets, a 20-fold increase. Readers in Brazil are binge-reading web novels about Chinese office politics, while Spanish speakers are devouring stories about gaokao stress and tiger parents. The appetite was always there; we just needed the supply.

Consider Liu Cixin's success. The Three-Body Problem was an international sensation, not despite its Chinese elements, but because it tells a fundamentally compelling story. Yes, his prose is "pre-translated," but that's precisely why it translates well via AI. The cultural details (Cultural Revolution backdrop, Chinese academic politics) enhance rather than weigh down the sci-fi narrative. And AI translation is creating thousands more "Liu Cixin effects." Authors who write in accessible and plot-driven styles are finding their way to a global audience.

The very simplification that purists decry, "We're losing authenticity!" has an undeniable upside. They ignore that 99.9% of non-Chinese readers never had access to that authenticity anyway. Before AI translation, maybe 200 Chinese works got English translations per year, hand-selected by Western publishers who thought they knew what global audiences wanted. Those who argue "Human translators are better!" Sure, when you can find them. Research shows human translators produce slightly higher accuracy scores than AI, but there are maybe 50 professional Chinese-English literary translators in the world versus millions of works waiting for translation. It's like arguing that handmade shoes are better than factory-made ones while most of the world goes barefoot.

Just like subtitles made foreign films more accessible, AI translation is changing how we read foreign literature. Netflix didn't make Squid Game worse by subtitling it; they gave it a global audience. AI translation is doing the same for Chinese literature, flaws and all.

Last week, I read an AI-translated Chinese web novel about a time-traveling programmer who debugs historical events. It was ridiculous, poorly translated, but absolutely addictive. I never would have discovered it through traditional publishing.

What Chinese stories are you discovering through AI translation? Are we losing something essential, or finally accessing what was always there?

This morning, I overheard my grandparents discussing my cousin’s latest gaokao mock exam. It went something like this:

Grandpa: “He still has two years.”

Grandma: “Which university does he want to attend?”

Grandpa: “The one in Hong Kong. It’s a pretty good school. But the cutoff score is so high. He needs at least a score of 640 or more!”

Grandma: “No one said it’d be easy. I heard he’s been waking up at 6am every morning this summer to study.”

Conversations like this play out in millions of households each year. Every June, thirteen million Chinese students sit for the two- to three-day gaokao, the college entrance exam that can decide their future in a single score. For centuries, exams have been the crucible through which Chinese ambition and anxiety are forged. Yet in recent years, though, even as parents strategize and students cram, one thing is certain: during gaokao season, certain features of AI tools are disabled. The restriction is meant to prevent cheating, yet at the very moment when Chinese teenagers face the most important test of their lives, the most powerful tool of their generation is locked out. China may champion AI innovation on the world stage, but in its own education system, it remains a source of deep suspicion.

Historically, Chinese education has rested on the twin pillars of diligence and memorization, which generations have called 苦读, or “bitter studying.” Beneath the surface debate over AI lies a deeper, generational expectation that children must retrace the same path of hardship their parents endured, learning endurance, grit, and the discipline to push through when nothing comes easily. To the older generation, AI tutoring tools would feel like a hollowing out of moral substance, as if discipline itself can be outsourced. Yet for the younger generation, raised in an economy where competition is fiercer than ever, not leveraging this new technology can often mean being left behind.

When we talk about the politics of AI and education in China, we often see how the state wants to be number one in AI but fears its social impact at home. While that’s true, it only sweeps the surface. The gaokao is one of the few institutions in China that still carries the aura of fairness. Corruption scandals have rocked other parts of life, but the gaokao retains a reputation, however imperfect, as a meritocratic pathway. Imagine a rural student memorizing formulas with pen and notebook, while an urban student has a personalized AI tutor simulating test conditions and correcting errors instantly. Both sit the same gaokao, but their journeys to the exam room could not be more different. But honestly, if AI provides some students an advantage before the exam, that’s a different problem, but at least during the four days of testing, the state wants everyone in the same boat: pen and paper, sweat and nerves.

Beyond the classroom, AI apps are shaping how students learn and think. Each interaction generates massive, granular data that investors, schools, and even parents can monitor. AI platforms now claim they can forecast a student’s likely gaokao score months in advance. In practice, this creates a new kind of pressure, one where a student is no longer only competing with classmates but with a number generated by an algorithm, a kind of algorithmic fatalism. Some students see it as motivation, but many feel that their future has already been calculated and that the system knows before they do whether they will succeed or fail.

The bigger question is what happens when students trained under these restrictions graduate into a world where their peers abroad have always treated AI as second nature. The gaokao preserves a level playing field domestically, but globally, its graduates may face a new kind of inequality. For a generation trained to succeed without AI, the ultimate test may no longer be a national exam but how they compete in a world where AI is second nature.

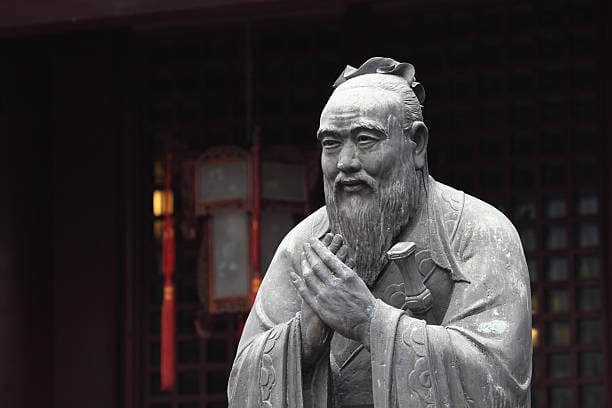

What a 2,500-year-old teacher can tell us about AI, dialogue, and the power of words

I first encountered Confucius in middle school, through freshly printed versions of The Analects. The Confucius Analects, a slim collection of dialogues between the philosopher and his students, revealed to me one thing about Confucius: he often adjusted his answers depending on who was asking. At times, he spoke in riddles and parables; at times he contradicted himself out of care for the student before him. In one case, he told Zilu to act immediately. When Ranyou asked the same question, he told him to wait. Two and a half millennia later, we call this practice prompt engineering. If history tells us anything, it’s that the words we choose and the questions we ask shape the answers we end up living with.

子路问:“闻斯行诸?”

子曰:“有父兄在,如之何其闻斯行之?”

冉有问:“闻斯行诸?”

子曰:“闻斯行之。”

公西华曰:“由也问‘闻斯行诸’,子曰‘有父兄在’;求也问‘闻斯行诸’,子曰‘闻斯行之’。赤也惑,敢问。”

子曰:“求也退,故进之;由也兼人,故退之。”

[Modern Translation]

Zilu asked, “When I hear a principle, should I put it into action right away?”Confucius replied, “If you still have your father and elder brothers above you, how could you simply hear something and act on it immediately?”

Later, Ranyou asked, “When I hear a principle, should I put it into action right away?” Confucius replied, “When you hear it, you should act on it.”

Gongxi Hua said, “When Zilu asked, ‘When I hear a principle, should I put it into action right away?’ you answered, ‘You still have your father and elder brothers above you.’ But when Ranyou asked the same question, you answered, ‘When you hear it, you should act on it.’ I’m confused, so I dare to ask for your guidance.”

Confucius said, “Ranyou tends to hold back, so I encourage him forward. Zilu tends to be too headstrong, so I restrain him.”

We can tie Confucian philosophy to today’s large language models through one shared element: dialogue. The conversations recorded in the Analects predominantly circle around questions of virtue and moral goodness. How can I be a better son? How can I achieve greatness? Am I capable of serving in government? Confucius adjusted his answers to each student’s temperament, phrased in ways that guided them toward the growth they needed most. In today’s AI labs, we’re doing something relatively similar. We’re aligning models so they can produce helpful, harmless, and honest outputs. That’s what reinforcement learning and human feedback (RLHF) really are: a back-and-forth “teaching” loop where human trainers mold the machine’s responses through rewards and corrections. You probably do this with your chatbot!

Before I get ahead of myself, anyone who has spent any amount of time with ChatGPT will know that the way you frame a task makes or breaks the output. If you asked it to summarize a passage, it’d probably return something stiff, academic, and robotic. If you asked it to sound like Shakespeare, it would break into verse. If you asked it to explain physics to a child, it would switch to simple metaphors. The key here is that different instructions produce very different tones; in other words, the outcome depends almost entirely on the words you choose at the start.

“If names are not correct, speech does not accord with truth, and affairs cannot succeed.” (Analects)

Confucius believed that language does not merely reflect society but manifests it. Words commit us to courses of action; misnaming distorts not only what we say but also what we do. This is why people in his time, and often in China still, are careful with speech in a way that contrasts with Western free expression.

In a similar sense, this is why Chinese AI companies today call their models “big models” rather than the familiar Western “large language models.” For example, Baidu explicitly markets ERNIE as a 大模型 (“big model”), and not an LLM. "Big models" refers to a worldview that emphasizes AI as scale, as magnitude, as nation-building. Meanwhile, Western naming conventions (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini) lean toward the individual or the mythical. Each and every word choice pinpoints what users would expect, what they can demand, and ultimately what the chatbot produces.

All this raises a provocative question: when we spend hours refining prompts, correcting outputs, and coaxing ChatGPT to deliver our ideal responses, does that make us the teachers of value? Specifically our moral values? Models inherit the biases, ethics, and priorities we encode into their training. And the question isn’t only whether AI can reason, but whose conception of virtue it's being trained to follow.

As prompting has grown more popular, research papers in recent years have increasingly focused on how to best prompt large language models. While that alone is a significant indication of its staying power, it also reflects our utilitarian tendency to exploit rather than to teach. After all, these chatbots were made to boost productivity and serve their useful purposes. Online forums are also filled with “prompt libraries” and one-liners designed to squeeze the maximum output from a model.

If we map Confucian pedagogy onto prompting, the act looks less like “hacking” per se and more like a form of moral instruction or a way of guiding intelligence toward harmony, balance, and proper conduct. Like a teacher who doesn’t simply extract answers from students, a successful prompt cultivates the student’s character, most often through dialogue. By that logic, prompting appears to be more like education than it is exploitation, and you can easily see this contrast in how the two cultures talk about AI (which also hints at where each culture believes AI should go). Prompt engineering in the West is often described as a trick or workaround. But in China, the language leans more toward cultivation: “training,” “guiding,” and “correcting.” This Chinese framing, whether consciously intended or not, situates AI within a longer tradition of shaping minds and aligning behavior, which is honestly more akin to raising a child.

When we call ourselves prompt engineers, we like to imagine we’re doing something revolutionary. But two and a half thousand years ago, Confucius was already showing us that the shape of a question shapes the shape of the answer and, more importantly, the shape of the student. A single phrase can push someone to act boldly or cautiously, to align with truth or to drift off course. That’s why China’s AI culture today feels different from Silicon Valley’s. And maybe prompt engineering isn’t the invention of the AI age at all. It may be a return to something Confucius already intuited: that the form of a question is not overlooked but carries within it the power to direct thought, constrain possibility, and prescribe a certain horizon of answers. If so, what we call “engineering” today is simply the latest expression of an older human practice. Specifically, it involves the intentional application of language to control intelligence, be it human or machine-based.

Confucius wasn’t just a teacher of men. He was the first prompt engineer.